Hello World¶

Java is installed, our IDE has a project open, we’re ready to write some code. In this step we breeze through a light treatment of many Kotlin concepts, all from the Python perspective.

The REPL¶

Python has an interactive interpreter, aka REPL, which makes it easy to play around and learn. It’s a dynamic language, so this makes sense. As it turns out, Kotlin (in IntelliJ) has a REPL also.

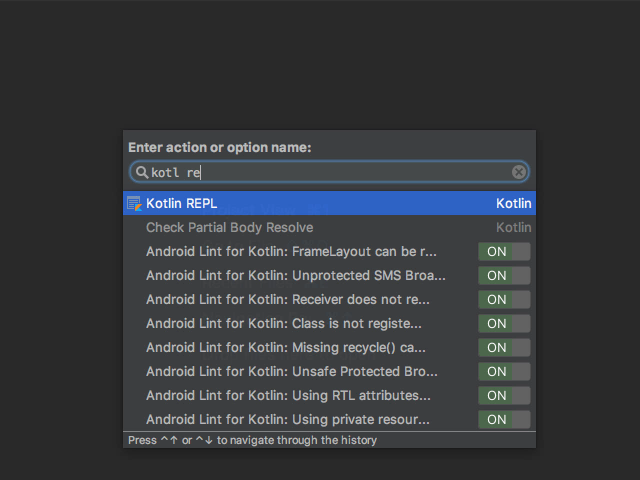

Opening the Kotlin REPL is easy. You can use the Tools | Kotlin menu

or search for the action:

In Python we have the Python Console tool window, which opens the

Python interpreter in the context of your project. The Kotlin REPL is

the same idea.

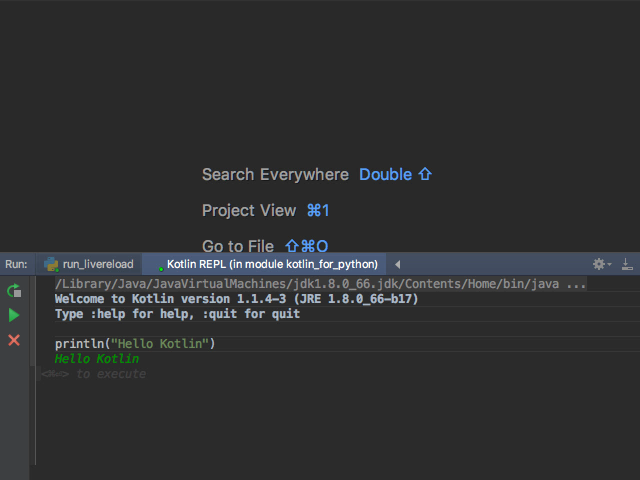

Let’s type in some code:

Here we typed a line of Kotlin code and executed it with Cmd-Enter (macOS.)

We could have clicked the green play button, which triggers the run action

just like Cmd-Enter. Kotlin evaluated our line, letting Kotlin/Java do

a mountain of machinery behind the scenes.

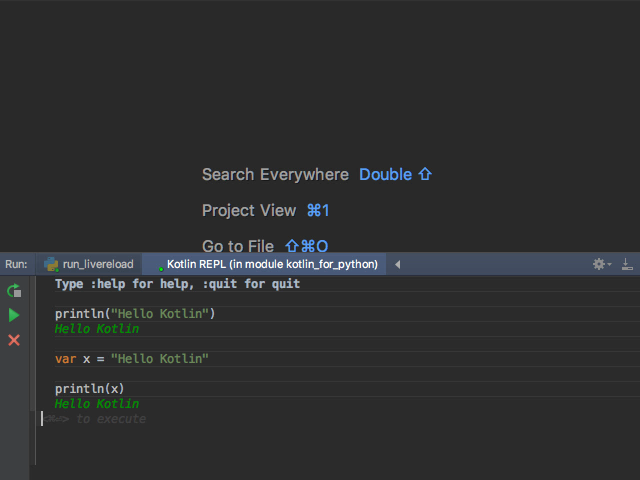

The REPL can handle multiple lines:

As this is our first foray into Kotlin, let’s analyze this small bit of code from the Python perspective:

1 2 | val msg = "Hello Kotlin"

print(msg)

|

- We declare variables with

var(which allows re-assignment) orval(which is like a constant). Python doesn’t havevar. - Double quotes for strings

- No semicolons!

- A print function (like Python 3, but unlike Python 2)

All in all…other than var, it’s exactly like Python.

Click the red X to close the REPL and let’s start writing some Kotlin code.

First File¶

In Python, we’d make a .py file and start typing in some code. From

Python’s semantics, there are almost no rules about the file itself – name,

location, etc. For example, here is a minimum hello_world.py:

1 2 | # Python

print("Hello World")

|

We can start the same in Kotlin. IntelliJ has created a src directory

for you. Right-click on that and create a file at

src/hello_world/hello_world.kt:

1 2 3 | fun main(args: Array<String>) {

print("Hello World")

}

|

Here’s the equivalent Python file to mimic a main function:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | # Python

def main():

print("Hello World")

main()

|

Python uses def to define a function, Kotlin uses fun. We’ll talk

more about this in Functions.

The Kotlin file shows the standard Kotlin “entry point”: by convention,

the file being executed must have a function named main which accepts

a single argument, an array of strings. Kotlin itself then calls this

main function. This is a bit similar to the common (but not required)

Python run block. For example, this file in Python might look like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | # Python

def main():

print("Hello World")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

|

In this Python example, we had to both detect that the module was being run (instead of imported) and then call the appropriate “main” function.

We saw strong typing in the Kotlin function definition. Python of course has typing, but it is at run time and is inferred. (We’ll discuss type hinting in the section on Variables and Types.)

Time to run this, which really means, compile and execute. If you’re

familiar with PyCharm run configurations and gutter icons, it’s

similar. Click the Kotlin symbol in the gutter for line 1 and select

Run:

[TODO screenshot of running it]

Note

IntelliJ prompted us to Run 'Hello_worldKT'. What’s

Hello_worldKT? Answer: To make Java happy, Kotlin generated

a Java class behind the scenes.

When you clicked this, there was a lag that you don’t get in Python. This the build/compile phases from Java. It’s incremental, so it is faster after the first time.

Now that we’ve run our program, let’s breeze through some head-to-head comparisons on a few programming language basics.

Braces¶

This is the most obvious point: like most other programming languages, Kotlin delimits blocks with braces. Python uses indentation.

Quotation Marks¶

Switching between languages, or even projects, means swinging back and forth between single versus double quotes for strings. For example, TypeScript prefers double quotes, but ReactJS ES6 applications prefer single quotes. And they are both (sort of) JavaScript!

Python’s PEP 8 style guide doesn’t prefer one or the other, but

most Python projects seem to use single quotes. In fact, Python has

triple quoted strings!

1 2 3 4 5 | # Python

hello = 'world' # best

hello = "world" # ok

hello = """

world""" # triple

|

Java (and Kotlin) use a single quote for a single character value and double quotes for strings. Triple-quotes indicates a raw string:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | // Kotlin

val c = 'C' // character

val hello = "hello" // string

val raw_string = """

line 1

line 2

"""

|

Comments¶

Kotlin supports the two familiar styles of comments: end-of-line and block comments:

1 2 3 4 5 | val hello = "world" // Kotlin line comment

/*

Let's leave out

these lines

*/

|

IntelliJ (and thus PyCharm) as an IDE makes it easy to comment and uncomment

lines and selections with Cmd-/.

Python, of course, only uses hash # as the comment symbol,

with no block comments:

1 2 3 4 5 | #

# Python multiline commments

# have a lot of hashes.

hello = 'world' # Python comment

|

Variables¶

Python doesn’t have any special syntax for declaring a variable. You just assign something:

1 2 | # Python

hello = 'world'

|

Kotlin, though, does. In fact Kotlin has two keywords: one to declare a read-only immutable value, and one for a mutable variable:

1 2 3 | // Kotlin

val hello = "world" // Read-only, val == value

var hello = "world" // Can be re-assigned, var == variable

|

Where’s the Java-style type noise? Good news – Kotlin can infer the type. The above is the same as being explicit:

1 2 | // Kotlin

val hello: String = "hello"

|

Also, like Python, you can initialize a variable without assigning it:

1 2 | // Kotlin

var hello

|

Of course with Python 3.6 variable annotations, we can make Python look much more like Kotlin. We cover this in the section on Variables and Types.

String Templates¶

Python – the “there should be one way to do things” language – actually has several ways to do string templates:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | # Python

msg = 'World'

print('Hello %s' % msg) # Original

print('Hello {msg}'.format(msg=msg)) # Python 3 (then 2)

print(f'Hello {msg}') # Python 3.6

print(f'Hello {msg.upper()}') # Expressions

|

Kotlin also has string templates with expressions:

1 2 3 4 | // Kotlin

msg = "World"

print("Hello $msg")

print("Hello ${msg.toUpperCase()}")

|

Functions¶

Python functions can be very simple:

1 2 3 | # Python

def four():

return 2 + 2

|

No curly braces, just indentation. Kotlin’s simplest case is pretty close:

1 2 3 4 | // Kotlin

fun four(): Int {

return 2 + 2

}

|

Kotlin adds the curly braces and has to define the return type (which can be omitted if there is no return value.)

But watch this – a function expression:

1 2 | // Kotlin

fun four() = 2 + 2

|

Admit it, that’s pretty sexy. Function expressions are a big new idea which we’ll cover in the section on Functions.

Passing in function arguments is straightforward in Python:

1 2 3 | # Python

def combine(x, y):

return x + y

|

How does that compare to Kotlin?

1 2 3 4 | // Kotlin

fun sum(a: Int, b: Int): Int {

return a + b

}

|

You have to provide the type information on the function arguments and return value.

Conditionals¶

Let’s take a quick look at things like conditionals and looping. In

Python, an if/then/else is straightforward, with use of indentation:

1 2 3 4 5 | # Python

if a > b:

return a

else:

return b

|

Kotlin looks quite similar, adding parenthesis (optional in Python) and braces:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | // Kotlin

if (a > b) {

return a

} else {

return b

}

|

We’ll cover more on this in Conditionals.

Looping¶

Let’s compare looping over sequences. Simple Python example:

1 2 3 4 | # Python

items = ('apple', 'banana', 'kiwi')

for item in items:

print(item)

|

Here we’ve created an immutable sequence (a tuple) in items. We looped

over it in the most basic way possible.

In Kotlin, we have a different construct for making the sequence. Looping

is similar, though we use a parentheses after for:

1 2 3 4 5 | // Kotlin

val items = listOf("apple", "banana", "kiwi")

for (item in items) {

println(item)

}

|

In this case we used println. In Python, the print function always

makes a newline unless you ask it not to.

Both Python and Kotlin have rich and interesting control structures, giving both power and terseness. We’ll see more in Sequences and Looping.

Classes¶

Lots to cover later on this, so for now, let’s just view the simplest couple of cases. The minimum in Python:

1 2 3 | # Python

class Message:

pass

|

In Kotlin:

1 2 | // Kotlin

class Message

|

It’s hard to tell which of those have the smaller conceptual density. And who cares – they’re both tiny! Let’s add a constructor, some variables, and methods. First in Python:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | # Python

class Message:

greeting = 'Hello'

def __init__(self, person):

self.person = person

def say_hello(self):

return f'{self.greeting} {self.person}'

|

This class has a “constructor” with one argument, which is assigned as an

instance attribute. The class attribute of greeting is used in a

method say_hello which returns an evaluated f-string.

How about the type hinting flavor for Python 3.5+?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | # Python

class Message:

greeting = 'Hello'

def __init__(self, person: str):

self.person = person

def say_hello(self) -> str:

return f'{self.greeting} {self.person}'

|

Let’s see this in Kotlin:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | // Kotlin

class Message(val person: String) {

val greeting = "Hello"

fun sayHello(): String {

return "$greeting $person"

}

}

|

That constructor syntax, right in the middle of the class name line, is unusual and cool. It helps to reduce the typing versus Python’s constructor. We’ll go into more depth on this in the section on Classes.